Who was Michael ”the Beer Hunter” Jackson

Text Martyn Cornell Illustration Victor Jönsson

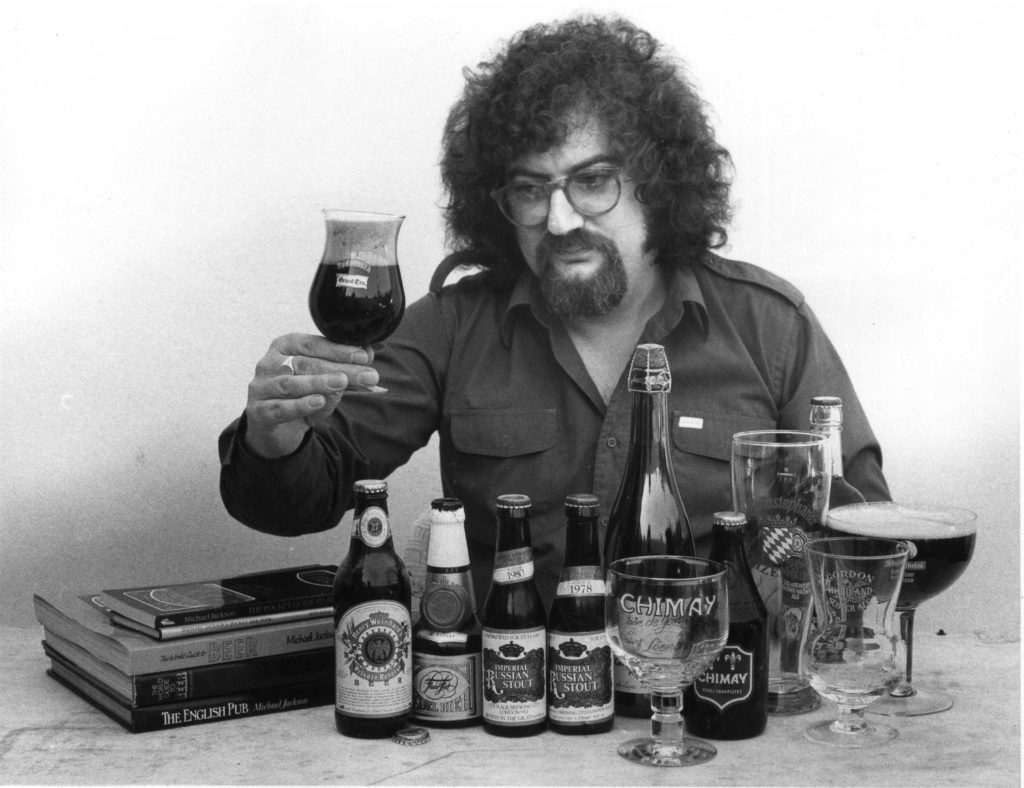

“My name is Michael Jackson, and I’m on a world tour,” the short, portly, bearded Yorkshireman used to tell his audiences. “But I don’t dance, I don’t wear one white glove and I don’t drink Pepsi.” Like his American namesake, however, Michael Jackson was a global superstar – at least in the world of beer, where, ten years after his death in August 2007, he is still regarded as probably the most influential beer writer ever. Jackson’s books and articles opened up drinkers and brewers both in his native Britain and across the Atlantic to possibilities far beyond mass-produced lagers and ales. Perhaps most importantly, he was the person who coined the term “beer style”, categorising beers in a way that, 40 years on from when Jackson started using “style” as an easy-to-understand way of labelling and describing different beers, is now ubiquitous, but was revolutionary at the time.

Today, a decade on from when he died of a heart attack at his home in West London aged 65, many people still regard Jackson as a pivotal, crucial figure in the world of craft beer, far more important than any actual brewer. Ray Daniels, founder and director of the Cicerone Certification Program in the United States, which educates and certifies beer sommeliers, and currently has around 85,000 certified beer servers and 2,800 certified beer cicerones in 50 countries, declares: “Michael Jackson is, quite simply, the foundation upon which modern craft beer is built. There’s not a single person who started a brewery or wrote about beer before 2000 who was not directly influenced by his work. And I’d argue that everyone since then has been either directly or indirectly influenced by him as well.

“Through his books, periodical writings and presentations, Michael taught us about beer. More importantly, he taught us how to think about beer. When he started his work, global corporations defined how virtually every consumer thought about beer. He discarded the storylines crafted by big beer and instead found compelling stories and intriguing characters in the small, struggling brewers of the day. In so doing, he gave us a new paradigm. His was based neither on producer size nor buyer psychographics. Rather he delved into the personality of the beer’s creator and the quirks of its production. In addition, he focused attention on describing the flavour of each beer in a meaningful but accessible way. Ultimately this produced profiles of true craftsmen, giving us tools for sussing out authentic explorers from those who pursued the making of beer simply as a business.”

Daniels’s views are baked by the Danish brewer Anders Kissmeyer, who says: “Michael Jackson was in the eyes of the entire Scandinavian brewing scene and myself a guiding star and a tremendous inspiration due to his extremely deep insight into the universe of beer, his never failing enthusiasm for crusading on behalf of good beer, and – last but not least – his ability to communicate his always interesting and well-founded views on all things beer related to a very broad audience. I believe that the craft beer revolutions all over the world would have been slower and less powerful had there been no Michael Jackson.

“My first personal encounter with Michael was at the first ever Copenhagen Beer Festival back in 2001. I had obviously heard a lot about him in advance, but I was still amazed by the way he conducted himself. Although courted as had he been a Roman Emperor by a score of dedicated Danish fans, he still took the time to talk to anyone who approached him. It was like our very, very young craft beer scene was granted a holy blessing by Michael’s – at that time the undisputed world champion beer guru – appearance and encouraging comments to us.”

Strangely, this hugely influential figure in the world of beer only began writing about the subject by chance. Michael Jackson was born in Wetherby, near Leeds, in 1942. His grandfather, Chaim Jakowitz, had emigrated to Yorkshire from Kaunas in Lithuania, and Michael’s father, Isaac, a lorry driver, had anglicised the family name to Jackson. Michael had decided at the age of 12 that he wanted to be a journalist, and began his career in writing as a 16-year-old trainee reporter on a local newspaper in Yorkshire, the Huddersfield Examiner. Journalism was a notoriously boozy profession before the arrival of computers (which are impossible to work while tipsy), but Jackson had actually already started drinking beer while still at school: “Halves of Hammond’s Mild, which was all I could afford. I drank partly because I knew that great writers drank, and I wanted to be a great writer; partly to see if they would serve me,” he revealed in an interview in 1992.

Later, after stints on newspapers in Newcastle upon Tyne and Edinburgh (where, aged 19, he drank his first malt whisky, a 12-year-old Glen Grant, in the Canny Mans bar in Morningside, and fell in love with that drink too) he moved to London and worked on a left-wing daily newspaper, the Daily Herald, before, in 1968, becoming the editor at a newly launched trade magazine for the advertising industry, Campaign.

After other journalistic jobs, including being an investigative reporter for a television programme called World in Action, he was asked in 1976 by a publisher to step in and supply the words for a glossy, heavily illustrated book called The English Pub, after the person originally tasked to be the author failed to deliver a manuscript. The success of that book led the publisher to ask if Jackson would perhaps write a similar big, glossy book on the subject of beer.

He was probably the perfect person to be given the job: meticulous, inquisitive, organised, a tremendous interviewer, a natural storyteller, and already very interested in the subject. Jackson had learnt there was more to beer than English mild and bitter and Irish stout while on a visit to the south of Germany in the mid-1960s, where, he wrote later, he had spotted “old ladies in hats” drinking what he discovered was the then distinctly unfashionable Bavarian wheat beer, in the distinctively tall, vase-shaped glass, decorated with a slice of lemon. Later, working as a journalist in Amsterdam after leaving Campaign, he was reporting on a carnival in a village in the south of the Netherlands for a feature article, called in on a local inn for a drink and tried a Belgian Trappist beer for the first time. The next day he crossed the border into Belgium itself and began exploring that country’s beer culture, from strong pale ales to sour geuze to fruit lambics.

These experiences led into the World Guide to Beer, published in 1977 at the cost of “several thousand pounds in phone calls, letters, telegrams, travel and research assistance”, Jackson revealed later. It was, at the time, the most comprehensive guide to the drink ever written, with chapters covering beers that were almost completely unknown outside their native borders, from Cooper’s Sparkling Ale in Australia to sahti in Finland. The book came out at a time when, in Britain, interest in beer was starting to boom as the Campaign for Real Ale widened drinkers’ horizons, while in the United States the first of what would eventually be an explosion of new small breweries, the New Albion Brewing Company, had just opened in California. Mitch Steele, currently brewmaster at the New Realm Brewing Company in Atlanta, Georgia, and previously with Stone Brewing in California, says: “Back when I was starting out in a pub brewery, San Andreas Brewing Co, in Hollister, California, very few people in the US knew much about the beer styles of the world. Homebrewers, who by and large were the people that were starting brewpubs and breweries at the time, had learned almost exclusively from British homebrewing books, so the beers most of us made were English-inspired ales. We all looked at Michael Jackson with extreme reverence – he had travelled the world and written about so many different types of beer, and really was the first person to categorise the beer styles of the world with names and descriptions of what the beers should be.

“His World Guide To Beer was my bible for many, many years, certainly well into the late 1990s. I used that book all the time when I was in charge of new products at Anheuser-Busch, I used it to develop recipes, and I used it to educate the team at AB, because all they really knew was American and German lagers. Later, Michael’s Beer Companion book further defined beer styles and became an excellent resource.”

Another young brewer heavily influenced by Michael Jackson was Alastair Hook, who founded Meantime Brewing Company in Greenwich, South East London in 2000. Hook says: “When Michael published his Pocket Guide to World Beer around about 1980, very few people wrote about beer. As an 18-year-old I used it as a travel companion for a trip to Europe and it was my main inspiration that resulted in a career dedicated to beer. What is remarkable is that I know hundreds of middle-aged brewers who have been part of the modern beer revolution who were all inspired by Michael and his work. He brought the world of beer to life, pretty much single handed. A generation of new brewers disrupted the market as a result. The incredible choice available across the brewing world is down in no small part to his even-handed but inspirational writings.”

Jackson’s other huge influence was on the vocabulary of beer. Before the publication of The World Guide to Beer, books talked about “divisions”, “species”, “kinds”, “varieties”, “types”, “classes” and “families” of beer, but never “styles”. In The World Guide to Beer, however, Jackson devoted a section to what he called “The classic beer styles”, though he still differentiated between “beer styles” and “beer types”, saying: “If a brewer specifically has the intention of reproducing a classical beer, then he is working within a style. If his beer merely bears a general similarity to others, then it may be regarded as being of their type.”

Michael Jackson, furthest left, pictured at the Poperinge Hop Museum in West Flanders with other British beer writers in 1988. Just behind him is Roger Protz, long-standing editor of the Campaign for Real Ale’s Good Beer Guide, third row down, left is Tim Webb, author of a number of guides to Belgium beer, and Martyn Cornell is second row down, on the right.

In later books, he refined this idea. in 1982 he produced the first of a long series of Pocket Guides to Beer which still had a chapter headed “Types of Beer”, though the individual entries frequently referred to “style”, such as Bière de Garde, “This regional style of northern France”. In addition the book’s blurb described Jackson as “the world’s leading authority on beer styles”. The big push to the idea of beer “styles” came when the extremely influential American beer writer Fred Eckhardt seems to have picked up on Jackson’s terminology in 1989 and run with it in his self-published book The Essentials of Beer Style: A Catalog of Classic Beer Styles for Brewers and Beer Enthusiasts. This, and Jackson’s books, were hugely important in forming the way American homebrewers thought about beer categorisation, and fed into both the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) and the rapidly expanding microbrewing movement in the United States.

When, subsequently, beer “appreciation” websites such as Ratebeer.com (founded 2000) sprang up in the US, they naturally used the “beer styles” ideas pioneered by Jackson and used by the BJCP to help their contributors categorise the beers they were rating. In 1997, Jackson told All About Beer magazine: “I think I was the first person ever to use the phrase ‘beer style’. The next thing was to try to define what they were, which lots of people have done since, but I think I was the first person. But then my focus became really to talk about, to try to describe the flavours of beer. When I was first writing on beer, nobody else was describing the flavours in beer. It’s very frustrating when you read old books on beer.”

Some commentators find difficulties in the way Jackson is still idolised, and feel other important pioneers are being forgotten as a result. The Canadian beer blogger and writer Alan McLeod says: “The problem is not so much Michael Jackson and the degree to which he influenced good beer. It’s that he has become code for the foundations of micro-brewing and, after his death, the rise of craft brewing. If we read a bit we come to understand that people like Peter Austin [a British microbrewing pioneer] and Bert Grant [founder of another influential US West Coast microbrewery] were well down the path towards good beer before Jackson came on the scene, as were other beer writers. Jackson was able to ride the wave of greater interest in good food and globalism in the 1970s and 1980s and, in return, make good beer attractive in that context. But then, the simplicity of his agreeable construct of “style” was taken by the BJCP and turned into a complex mess that today’s new brewers have largely left behind in favour of individual expression as they raid not only the entire grocery store but also the great wild world in search of adjuncts and flavourings.

“One of the greatest disappointments for me is how little his actual writing is referenced. Often it takes you in directions quite different from what his supposed disciples would have us believe. This is especially puzzling given how much of it is freely available on line. In the end, he is a great figure in the popularisation of good beer. But he was not alone and many who also played important roles are too often lost in his shadow.”

For younger fans of beer, Jackson is inevitably less relevant. The award-winning English beer blogger Jessica Boak, who writes with her partner, Ray Bailey, says: “Michael Jackson is where Ray and I started. We had a copy of one of his less distinguished books, very photo-heavy, and I planned a series of Bavarian holidays around it. It was on one of those, in 2007, with that book on the table in front of us in a Regensburg beer garden, that we decided to start blogging. But we never got to meet him and don’t have that personal connection to him that seems to be shared by many better established beer writers.

“To us, he does seem less important these days. We, personally, don’t need the same kind of guidance and the world has changed a lot since 2007. Beer geeks know a lot more, and demand a lot more. Having said that, we are always delighted to find an article of his in an old magazine and the quality of his prose, novelistic, witty, has arguably still to find a match. If there is a canon of great beer writing his work is an essential part of it.

“He was the leader of the pack for so long that, if he was still around, he’d no doubt have adapted and stayed on top. In some ways, and I hope this doesn’t sound terrible, his passing created room for other writers to grow. Still, there is sometimes a feeling that ‘the scene’ is missing a leader.”

There is also, among many, a feeling that Jackson died at exactly the wrong time, when the beer scene globally was about to explode into an enormous variety of new small breweries, from Argentina to China, and all sorts of new beers. In Alastair Hook’s words: “The brewing world has changed from that of a few brewers monopolising choice, brewed in some far-away place, to a localised offering of vastly improved choice. In many ways the endless brewery closures and mergers of the 20th century are being reversed, and sense is being brought back in to the beer industry. Michael was the catalyst for all of this, and we all miss him hugely.”

”I am not drunk” – Ten years before his death, Michael Jackson was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, something he told in an interview with Daniel Shelton (Shelton Brothers) just weeks before he died. He also tell Daniel that he wants to write a book about his illness “I’m not drunk”. You can see the interview here.